PCT (left), CDT (middle), AT (right)

A tiny fraction of hikers actually pursue and complete a thru-hike. However, those that have completed one must answer the inevitable question - "what's next?". For these trail-hardened souls, hiking has become a way of life, possibly a lifelong passion, and completing a single long-distance trail is not enough. Pursuing the "Triple Crown" becomes the next level.

The Triple Crown of hiking is a thru-hike trifecta that includes the three most prominent long trails of the United States - the Appalachian Trail (AT), the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) and the Continental Divide Trail (CDT).

Completing the Triple Crown is not an easy feat. You must walk a total of nearly 8,000 miles across 22 states with one million feet of cumulative elevation gain. It is unofficially estimated that only about 600 people have actually hiked the Triple Crown. However, ALDHA-West has only officially recognized 334 Triple Crowners.

The first Triple Crown hike was completed by Eric Ryback in the early 1970s before there was even a triple crown and the PCT was still in its infancy. One of the most notable Triple Crowners in recent years is Heather "Anish" Anderson who is the second female to complete a Double Triple Crown (whoa!). She currently is attempting her third Triple Crown which she aims to complete in a single calendar year. Most people are not as ambitious and break up the hikes over a few years so they can hike in the warm season.

Lets go over what makes some of these trails unique from one another.

APPALACHIAN TRAIL

The AT is known for its roots, steep climbs, lush green forests and historical trail community.

Length: ~2,190 miles

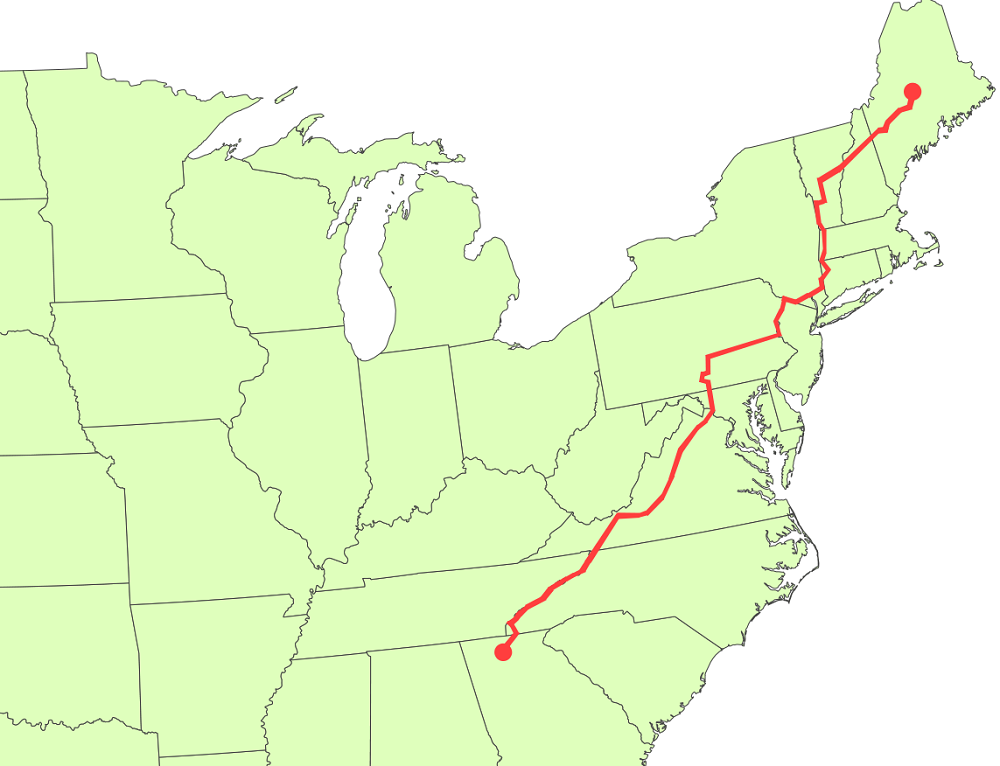

Start and Finish: Southern terminus is Springer Mountain in Georgia and northern terminus is Mount Katahdin in Maine. Travels through 14 states.

Time to complete: 5 to 7 months

Highest Elevation: 6,643 feet, Clingmans Dome in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Elevation Change: 917,760 feet with an average of 420 feet/mi

Annual Thru-Hiker Numbers (2017): 3,377 started at Springer Mountain and 685 finished at Katahdin (19% finish rate); 497 started in Maine and 133 finished in Georgia (27% finish rate). Note this data is only from hikers who voluntarily registered their hike and completion with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

First Thru-hike: The Trail was completed in 1937. Earl V. Shaffer is the first documented thru-hiker who completed the trail in a single hiking season in 1948.

Geography and Terrain

The AT is the oldest and most traveled of the Triple Crown trails. The hiking-only trail travels through 14 states providing a diversity of terrain from the thick deciduous forests of the south, the rocks of Pennsylvania and the rugged alpine mountains of New England. The AT was designed as a hiking trail for city dwellers, so there is little to no access for bikes and horses. It is easy to follow thanks to the abundant white blazes and exceptional trail maintenance.

The AT is often called the "Green Tunnel" for the dense forest makes it feel like you are walking in a tunnel. There are scenic vistas between the long stretches of forest, but not as many ridge walks or open summits as the PCT or CDT. The trail tends to a roller coaster, going up mountains and then back down. Because it was built in the early 1900s, the trails are steep with very few switchbacks and weird routes that leave you wondering why the path goes that way. Because of its steep climbs, the AT is considered to be physically more difficult than the PCT or CDT.

photo credit: @reptarhikes

photo credit: @reptarhikes

Weather

The AT is relatively predictable with its weather. The temperatures are much more moderate, and there is rain... a lot. It is also very humid. Sometimes there is snow in Georgia (or Maine) in the spring (or fall), but these cold weather conditions are short-lived. Most people start with cold weather gear in the early spring and then send it home shortly after they start.

Food and Water

Except for parts of Maine, the AT is not as wild or remote as the PCT or the CDT. The AT crosses more than 500 public roads, and trail towns are close to the trail making hitching easy. Hikers rarely have to carry more than 5 days worth of food and water sources are abundant. Unlike the CDT and PCT which favor "cowboy" and on-trail camping, the AT has more than 250 on-trail shelters for hikers to sleep at night or seek refuge from the rain, which occurs frequently.

Wildlife

Wildlife is common, especially bears, deer and of course, mice in the shelters that try to steal your food. Bears are a concern in the Smoky Mountains with shelters sometimes closed due to a nuisance bear harassing hikers for food. Ticks also are prevalent, and hikers should check themselves for ticks daily. In spring and early summers, hikers will encounter swarms of mosquitoes and biting flies as they move north.

Culture

The AT is the most social trail of the three in the Triple Crown. The large contingency of thru-hikers, the sharing of shelters and lots of trail towns create a social experience unlike any other. Even though they are hiking 20+ miles a day, hikers often form groups called trail families, that hike together or meet up at the shelters and trail towns. It's hard to be alone on the AT if you camp at the shelters.

Trail Magic is common on the AT thanks to the trail's close proximity to the road and towns. This close proximity also makes it easy to hitch into towns. Trail names are serious on the AT. You are given one early in the hike, and that is who you become. Each shelter has a logbook which helps to build the community.

The AT is the most well known and has the most people of any of the three Triple Crown trails. It is popularized in both books and movies, most notably A Walk in the Woods, which inspire people to hike the trail or support those who are walking the trail. Most first-time thru-hikers chose to attempt the AT before tackling any other long-distance trail.

PACIFIC CREST TRAIL

The PCT is known for diversity in terrain and temperature - dry desert, high elevation, and temperate rain forest.

Length: ~2,650 miles

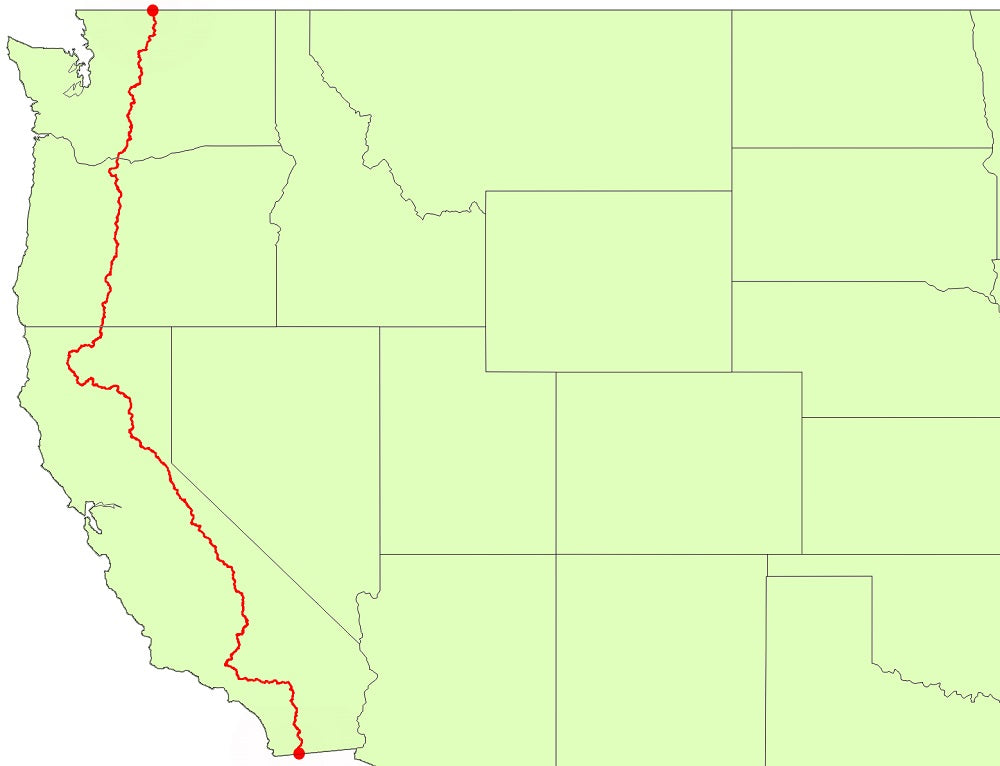

Start and Finish: Southern terminus is Campo, CA on the Mexican border and northern terminus is the US border at Manning Park in British Columbia. Travels through three states.

Time to complete: 4 to 6 months

Highest Elevation: Forester Pass, 13,153 feet

Elevation Change: 824,370 feet with an average of 309 feet/mi

Annual Thru-Hiker Numbers (2017): 3,496 NOBO + 438 SOBO permits issued; 491 reported completions from the Pacific Crest Trail Association.

First Thru-hiker: The trail was first conceived in 1932, designated a national scenic trail in 1968 and officially completed in 1993. The first thru-hiker was then 18-year-old student Eric Ryback who completed the trek on October 16, 1970.

Geography

The PCT stretches from Mexico to Canada traveling the length of California, Oregon, and Washington. The Trail was intentionally routed through as many protected areas as possible and nine of North America’s ecoregions. The trail is graded for hikers and horses, so the climbs are not as brutally steep as the AT. That doesn't mean it is easy - the trail starts in the desert which makes hiking in the hottest part of the day almost impossible. Most thru-hikers take a siesta in the afternoon, opting to get their miles in the early morning and late evening.

After the desert, the PCT enters the steep elevations, endless passes and ridge walks of the Sierra Nevadas. Though the mountains in the Sierras are higher than the Appalachian, the climbs are more manageable thanks to the switchbacks. You just have to watch out for elevation sickness as the elevation increases. Because you are on ridges so much, this section is beautifully scenic. The trail ends in the lush forests of the Cascade mountains. There are only a few stretches of "green tunnel" hiking and plenty of ridges with beautiful vistas in this section.

Most of the PCT is well marked, but it is not as well maintained or as heavily traveled as the AT. Hikers should come prepared with maps, compasses and GPS devices or apps on their phone to aid with navigation. They also need to secure a permit and carry a bear canister in the Sierras. Because of the more gradual terrain and the ridge walks, hikers can cruise on the trail doing 20-30 miles a day and finish within 4-5 months.

photo credit: westernpriorities.org

photo credit: westernpriorities.org

Weather

Overall, weather on the PCT can be described as variable. It is sweltering in the desert during the day with cool nights that are great for sleeping and hiking. Depending on the seasonal snowfall, there may be ice and snow in the Sierra Nevadas and in the Pacific Northwest. Temperatures are colder in these higher elevations as well. More specialized gear is needed on the PCT than the AT. Hikers may have to carry microspikes, ice axes and cold weather gear for long stretches of the trail. Forest fires are frequent in the summer so hikers may also have to contend with closed sections of the trail and thick smoke that makes it difficult to breathe.

Wildlife

Because it moves between the desert, the mountains, and the forest, the PCT has a wide variety of wildlife. Scorpions, lizards, and rattlesnakes are common in the desert while biting bugs and mosquitos are common in the Sierras and the Cascades. You also may see marmots, deer, elk, mule deer, mountain goats and maybe a bear or two in the northern part of the trail.

Food and Water

The PCT is harder logistically than the AT which has ample trail towns or a water supply nearly every five to eight miles. In the PCT desert, water is scarce. You need to fill up at water caches and carry more water through long, waterless stretches of the desert. Water becomes more abundant in the Sierras and the Cascades. Throughout the whole trail, there are greater distances between supply points, and overall there are fewer supply points. Carrying enough food for a 100-mile stretch is common. Hikers must have a resupply plan and send food ahead to specific resupply points on the trail. They cannot rely primarily on trail magic and town food.

Culture

The PCT falls in between the AT and the CDT. It is not as civilized a the AT and not as remote as the CDT. The most significant difference between the PCT and AT are the shelters. On the PCT, shelters are almost non-existent, and there are few gathering points, mostly water sources, on the trail where hikers convene to eat, sleep and share trail stories. As a result, hikers tend to get more spread out on the trail. There are enough hikers to find trail families if you want, but not so many hikers that resources are overloaded or the path is crowded. You can find solitude if you prefer. Trail names are given but they not as prevalent on the PCT as the AT.

Trail magic exists, but it is not as common as on the AT. There are groups of dedicated trail angels who are known to be in specific locations providing support, but random trail magic is rare. There also are many trail towns that are very supportive of hikers, but they tend to be further away from the trail. Hitches are longer and harder to get.

The PCT is growing in popularity, but it is not as well known outside hiker circles. It was relatively unknown outside the west coast until Cheryl Strayed’s book Wild hit shelves in 2012 and was made into a movie a few years later.

To read the complete thru-hiking guide to the PCT, visit this page.

CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL

The CDT is known for being rugged, wild and remote with only loosely-marked trails.

Length: ~3,100 miles

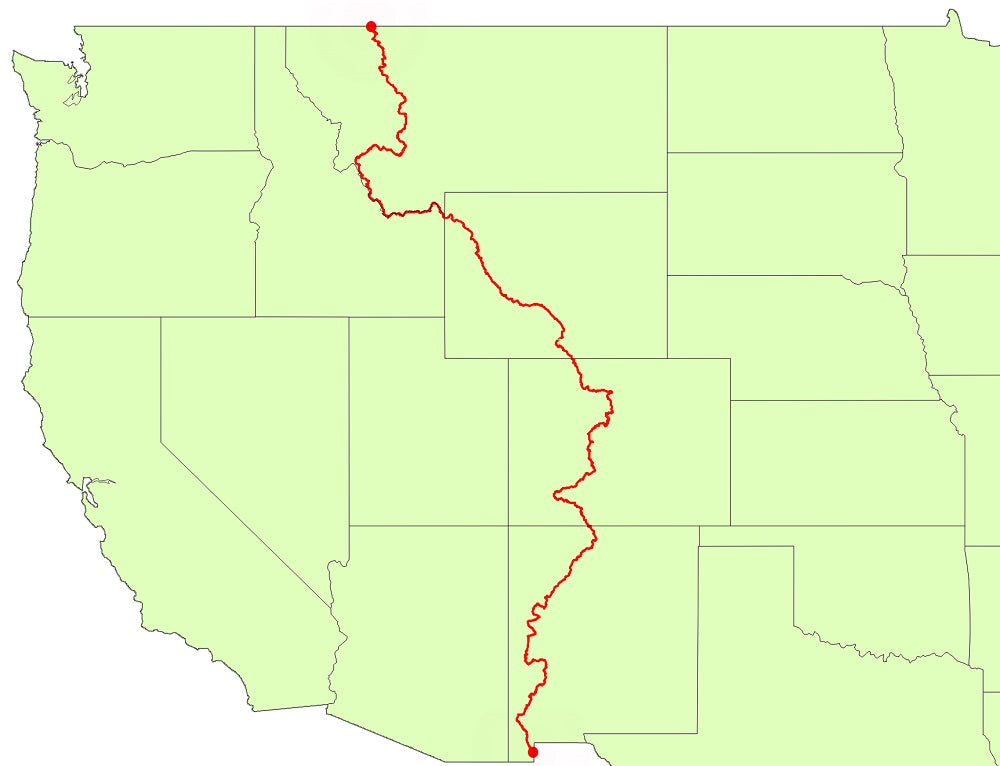

Start and Finish: Southern terminus is Crazy Cook Monument in the Big Hatchet Mountains of New Mexico at the U.S.–Mexico border and northern terminus is Waterton Lake, Glacier National Park, Montana at the U.S.–Canada border. Travels through five states.

Time to complete: 4 to 6 months

Highest Elevation: Grays Peak, Colorado, 14,278 feet

Elevation Change: 917,470 feet with an average of 303 feet/mi

Annual Thru-Hiker Numbers (2017): approximately 300 people attempt the trail with 81 reported completions.

First Thru-hiker: Designated a National Scenic Trail in 1978, but only 76 percent is completed and continuously connected. First thru-hiker was Eric Ryback who completed the trail in 1972.

Geography

Dubbed "America's most challenging trail," the Continental Divide Trail follows the Continental Divide through five states, beginning in the New Mexico desert and climbing to the high peaks and snowy summits of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. It traverses the Great Basin in Wyoming where it finally ends in the Big Sky country of Montana and Idaho. It passes through several national parks including Glacier, Yellowstone, and Rocky Mountain National Parks.

The trail is a mixture of dirt trails, dirt roads, and even paved roads. Though mostly a hiking trail, some of the CDT is open to horses, snowmobiles and mountain bikes. While the AT and PCT are completed trails, well marked and relatively well used, the CDT is unfinished. Only an estimated 76 percent of the path is completed, making it more of a "route" than a "trail".

As mentioned, the trail itself is not well marked and can be very difficult to follow. Hikers should bring a GPS device and, especially know how to use a compass and map for navigation. To improve the navigation, the Continental Divide Trail Coalition is blazing the last 750 miles in 2018 with the help of 50 volunteers.

photo credit: colorodadotrail.org

photo credit: colorodadotrail.org

Weather

The weather on the CDT will run the gamut. You will encounter 100-degree hot and dry sections in New Mexico as well as snow and freezing cold temperatures in the high peaks of Colorado. Lightning, hail, rain and high winds are all commonplace. Hikers need to bring adequate gear and clothing to handle the weather conditions of the section they are hiking and shoud plan to bounce clothes ahead as needed.

Wildlife

In New Mexico, the CDT crosses the open range, and grazing cows are everywhere. Rattlesnakes, lizards and other desert creatures are common in New Mexico. The majority of the trail is a rural mountainscape, so wildlife is abundant. There are black bear and grizzly bear, mountain goats, wolves, wolverines, mountain lions and more to contend with.

Food and Water

The CDT is much more difficult logistically than the AT or the PCT. Resupply points are few and far between with at least 5 to 7 days or more between towns. Not only are there are fewer towns compared to the AT and PCT, but the trail does not go near them. Because of the distances to the trailheads, it is hard to hitch into towns and their is almost no trail magic. Finding and paying for a shuttle is much more critical on the CDT.

The CDT is a relatively dry trail with long sections between water sources in every state. Guidebooks help to identify available water sources, but they may or may not have water based upon the seasonal snowpack and recent weather patterns. The Continental Divide Trail Coalition provides water source reports, but they are crowd-sourced and are only accurate when people submit their data. You sometimes can find water at electric windmills and cattle ponds, but these sources also are not 100 percent reliable.

Culture

Life on the trail on the CDT is much different than the party atmosphere of the AT or the casual friendliness of the PCT. On the CDT, most people are experienced thru-hikers who have their gear and hiking style dialed in. Because of the remote nature of the trail, people can't just jump on the path and start hiking on a whim. As a result, there are not as many people on the trail so you can walk for days or even weeks without seeing people.

Media references to the CDT are few and far between. The most popular book is Hiking the Continental Divide Trail by Jennifer Hanson. A chronicle of Hanson's solo thru-hike after her husband had to leave the trail.

Update: We've dedicated a fullguide to the CDT, including an interactive map, sectional overview, information permits, shelters and more. Check it out here.

650-Calorie Fuel

650-Calorie Fuel